The Four Stages of Disruptive Innovation Victimhood

By Jeffrey Baumgartner

Disruptive innovation is great if you are the disruptor, but nasty if you're the victim. One day you are running a mature industry with established products, a mature market and enough innovation managers running around your offices to pretend your business is innovative. The next day some smug young upstarts, in Silicon Valley or Mumbai, launch a crazy business that somehow makes your business seem obsolete. To make matters worse, you might not even realise you've been disrupted until it is too late and your stock value is falling faster than a brick dropped from a skyscraper. But don't feel bad, most business leaders are slow to discover they have been disrupted.

So, as a public service to potential victims of disruptive innovation, I am pleased to provide this explanation of the four stages of disruptive innovation victimhood. If you recognise that your business is at one of these stages, don't panic. Instead, you should ... well, you could ... hmmmm ... maybe you should panic.

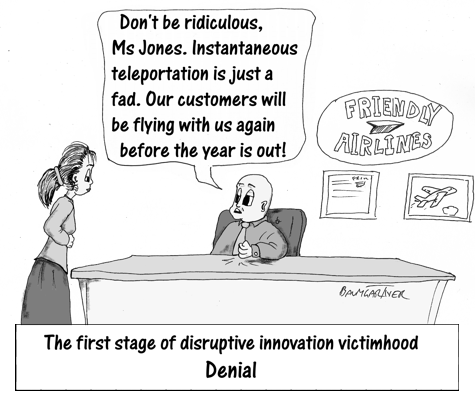

First Stage: Denial

The first stage of disruptive innovation victimhood is denial. First the blogs write about some silly business that will fundamentally change your sector. You laugh at it. What do bloggers or youngsters know about your business? You've been in the business since those entrepreneurs were in nappies (or diapers, if they are American entrepreneurs).

Then, the story makes its way into conventional press. First, you read about the disruptive upstarts taking over the market in Wired, but you do not worry much. You know the journalists at Wired are easily excitable. Soon, you start reading about the disruptors in the serious business press − like the Financial Times, Wall Street Journal, Fortune. Now you begin to question, not the future of your business, but the reliability and accuracy of the serious business press. This is because you are in denial. And this is a bad thing, because the longer you are in denial, the longer you fail to take action and the more likely you are to make a fool of yourself in the press and in public.

Look at it this way: if everyone in the world, except you and your management team, believe your business model is doomed, it is more likely that you and your management team are mistaken − and not everyone else in the world.

Second Stage: Fight back, ideally unfairly

Eventually, you realise that the upstart entrepreneurs actually have a business concept that threatens yours and you feel it is deeply unfair. You have been in the business for years. You know it upside down and inside out. You have spent millions in marketing over the years and you have lots of customers.

Well, you used to have lots of customers. Now they are leaving you for the disruptor's business in droves.

So, you decide to fight back, unfairly if necessary − and it probably will be necessary. Fortunately, one of the advantages of running a big, long established business is that you probably have a politician or two in your pocket. You take them to lunch at a posh restaurant. You complain about those nasty disruptors, remind the politicians about all of your employees who will be out of work if your business fails and then you mention that you are flying off to Scotland over the weekend for a bit of golf and there is some extra space on your company jet.

Before you know it, your politician friends propose legislation to make make doing business for the disruptors difficult or expensive or, ideally, both. This, for instance, is what the hotel industry is doing in response to AirBnB's success and the taxi industry is doing to try and slow down Uber's growing domination of their market.

If you are lucky enough to have monopoly power, or even near monopoly power, you can exploit that to make doing business really difficult for the upstart. You might do this by giving away free a similar product to the one the upstarts are flogging. Even if their product is better, your monopoly gives you direct access to a massive customer base. This is what Microsoft did when Netscape launched one of the first multimedia web browsers at a time when then Microsoft CEO Bill Gates was in the denial stage with respect to the potential of the world wide web. However, Bill Gates is nothing if not bright and he quickly realised he was wrong about the web. It was going to be big. Really big. So, he had his team throw together a second rate web browser which the company gave away with every installation of Windows. Netscape may have been a better browser. But downloading and installing was more difficult in those days and people were less computer literate. So, Microsoft Internet Explorer became the standard web browser and Netscape was bought up by AoL and eventually just sort of faded into oblivion.

Third Stage: Copy the Disruptors

If fighting back does not work, and unless you have monopoly power it usually does not, the next stage in disruptive innovation victimhood is to copy the disruptors. Unfortunately, by the time you realise this and launch a copy-cat product, it is probably too late. The disruptors already have a product out there and it is considered cool by the blogs, by the business press and by your ex-customers. Anything you belatedly make will lack that coolness.

Your company, meanwhile, seems old-fashioned, untrendy and boring − at least by the fan base of the disruptors. As far as the consumers are concerned, you don't get it, whatever "it" might be. One day soon, you can be sure the taxi industry will come up with some kind of Uber-like app for taxis. But it will be clunky and distinctly not as cool as Uber or Lyft or those other upstarts' product.

Or, to put it another way, think about all those cool photographers who use Kodak digital cameras.

Can't think of any? There's a reason!

Fourth Stage: Go Bust or Get Bought Out for a Pittance

Eventually the disruptors steal your business and become filthy rich. They are the darlings of the business world and you are the dinosaur. You bleed business until you can bleed no more and your company goes into receivership. If you are lucky, it might hold a small place in history.

Alternatively, your company might get bought out, for a fraction of its value a couple of years ago, by another industry that fancies your brand name or physical assets. But your company will probably fade into oblivion just as Netscape has done in the bowels of AoL.

Or possibly, just possibly, you will survive in some small way. Ilford was once a big name in the film industry and rightly so. They made great film, especially of the black and white variety. Fortunately there still exists a handful of traditional photographers who value the quality of film and enjoy the process of developing images. So, Ilford exists as a shadow of its former glory, providing quality film to artists and aficionados.

That's probably better than bankruptcy, but the pay is not nearly as good as running a global empire.

Avoiding Victimhood

Of course, given the choice between becoming a victim and avoiding that fate, most people choose the latter option and I am sure you would too. There are three things you can consider if you fear being the victim of disruptive innovation: out-innovate the potential disruptor, buy up the disruptor or exploit your monopoly position.

Out-Innovate the Disruptor

This option takes a little advance planning. You need to come up with your own disruptive innovation and bring it to market before any disruptors attack. This a great method to avoid disruptive victimhood. Unfortunately, it almost never happens for two reasons. Firstly, well established businesses tend to pretend to innovate rather than really innovate. Shallow brainstorms and suggestion schemes are great for incremental innovation, but lousy for big, exciting, breakthrough innovation. Secondly, even if someone in your business comes up with an idea for the next big disruption, you and your top managers probably won't recognise it.

Did you know that Kodak developed the first digital camera? Did you know Polaroid was an early experimenter with digital imagery? Both of these companies could have taken a market lead with the new technology and out-innovated the innovators. But, both companies rejected digital photography because they thought film was better − and it was, in terms of quality and profitability. However, their customers were not really buying film, they were buying tools to capture, save and share memories, something digital imagery does far better than film.

Buy Up the Disruptor

If you can get past denial quickly, you may be able to buy up the disruptive new company before it takes over the market, gets listed on the stock exchange and soon has a value 10 times bigger than yours even though they only have three employees. This is a strategy Mark Zuckerberg is following at Facebook. If any hot, new social media company hits the market, he opens his wallet and buys them up. People laughed when Facebook bought Whatsapp for US$19 billion. But, I reckon Mr Zuckerberg realised that if he left it be, Whatsapp might one day buy up Facebook for US$19. If you don't agree with me on this, I'd be delighted to chat with you about it. You can find me on Whatsapp.

Exploit Your Monopoly Power

Exploiting your monopoly power only works if you hold a monopoly. It worked for Microsoft in the 90s. It worked for state owned telecommunications companies for years. That's one reason most governments broke up those monopolies. If they had not done so, you probably would not even have the option of reading this on a smartphone.

However, if you do not already have a monopoly and some smug start up is stealing your business, this option is useless.

I Can Help - Sort of...

If this article has put you into a panic about the danger of a disruptive innovation destroying your business, please don't panic. You'll need your adrenaline for when the disruptor strikes.

However, I can offer a couple of small services that might help a wee bit. Firstly, I could come up with a half dozen disruptive ideas that could damage your business. They probably won't be realistic, let alone viable. But, they'll help you and your team think about potential threats from disruptive upstarts and that might help you develop and recognise bold, disruptive ideas. At the very least, it will help you devise strategies for dealing with disruptive innovation.

Alternatively, I could deliver this article in the form of a speech and put all of your colleagues into a panic. After all, why suffer alone?