Unauthorised Innovation

By Jeffrey Baumgartner

You work in a large company and have a crazy idea. You research it, develop it in your mind and become convinced it's a viable idea, but still a slightly crazy one. In most organisations, you have three choices. One, you propose the idea through proper channels knowing that it is unlikely to be approved and if it is, it will be much diluted from your proposal. Two, knowing this in advance, you do not bother proposing your idea as it will never be approved. Three, you simply do it; you implement the idea without seeking permission first. The third option is the riskiest, but it often the best way to realise a crazy idea. Let's call this option an 'illegal idea'.

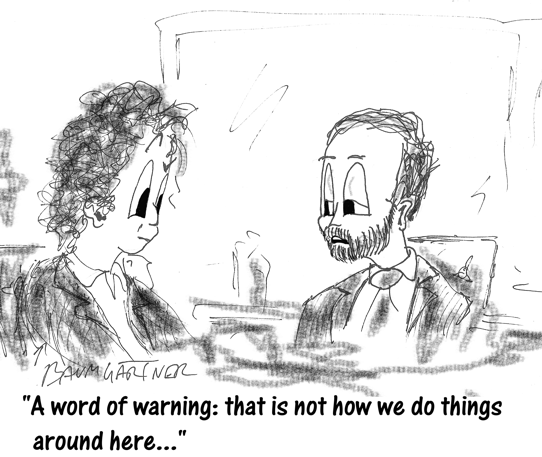

The funny thing with illegal ideas is when you get started, colleagues are likely to try and discourage you. They will warn you of the consequences of failure. They will tell you that's not how things are done in your organisation. If the idea succeeds, however, their attitude often changes. They buy into the idea. They may claim they always favoured the idea. Some may even try and take partial credit for the idea. It is best to allow these delusions to remain. At some point, you can no longer do it yourself. You need buy in. You need budget. You need support.

Of course, if the idea fails, the blame is likely to fall on you and there is no one else you can pass the blame onto. This is the risk of implementing an illegal idea. Oddly enough, you can even find yourself being rewarded and reprimanded for a successful illegal idea. This happened to me once. It is an amusing story, I believe.

Dr Ecommerce

In 1999, I was offered a temporary contract with the European Commission as an "Expert in the dissemination of information about electronic commerce to small and medium sized enterprises (SMEs) in the European Community" and moved from Bangkok to Brussels to perform the contract. Because I was the e-commerce guy in the e-commerce unit in the European Commission, when someone telephoned with a question about e-commerce, that call was usually forwarded to me. When someone sent a mail asking about e-commerce, it was usually sent to me. Among a team with lots of theoretical and legal knowledge, I was the only one with practical experience in the field.

Not surprisingly, there were a number of questions I was being asked again and again, which was tiring. I eventually created templates for a few very common questions. Other questions were bizarre.

In the past, I had written a business advice column for Business Review, an Asian magazine. People would send in questions and I would answer them, tapping into a small team of experts. The column was popular and I enjoyed writing it.

This experience inspired an idea. I could create an advice web site using a similar model. People could email (or use a form) to send in questions. I would answer them and publish most of them on the web site. Questions and answers could be organised thematically. Eventally, I could put together a board of advisors to help with questions outside my knowledge base.

I knew that some people would still send me questions directly, but if their questions had been answered on the web site, I could send them there with a link rather than repeat the answer. Very likely those people would find other useful information on the web site.

The web site, I reckoned, could be called "Dr Ecommerce". I shared my idea with a few colleagues. Some were amused, but doubted it would work. Some were dismissive. A few were in favour.

Entrepreneur from Bangkok

Once I had this vision, I should have written it up and submitted it up the bureaucratic ladder for approval. But, I came to the Commission as an entrepreneur from Bangkok where I had been running one of the Thailand's first web and multimedia production companies (hence my practical knowledge about e-commerce). I was not used to bureaucratic procedures. I was used to making decisions and acting on them quickly. Moreover, in the back of my mind, I think I knew that if I sought approval for my idea it would at best have been severely watered down in concept or it would have not been approved at all. The Commission is one of the most risk adverse organisations I've ever had experience with − at least it was at the time, my contract ended in 2001 and I've not worked with them since.

However, I had control of the e-commerce bit of the European Commission web site and started Dr Ecommerce without really getting permission. I initially posted questions that had been sent directly to me. But I also put up a contact email address and form. Soon, questions started coming in and I answered them.

The controversy also began.

Sort of Independent

As Dr Ecommerce quickly became popular, I decided that a little corner of the Commission web site with a long URL was not ideal. Remember, search engines were primitive at this time. Google was beginning to change that, but it was largely unknown in late '99 and early 2000. So, I bought the drecommerce.com domain name and put it on a web hosting company at my own expense. This gave me the freedom to move forward as I wished.

Dr Ecommerce took off. Questions came rolling in. The web site was written up in Time magazine, Foreign Policy magazine, Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung newspaper, ZDnet and elsewhere. It was a place where people could go for honest, practical answers − with a touch of humour − to all kinds of questions relating to the complexities of doing e-commerce across the European Union, EU legislation, international issues and more.

The result was a mixture of recognition, appreciation, animosity and reprimand all at once. I was widely praised by some people. I was invited to speak at conferences about e-commerce issues around Europe − especially as related to the complexities of cross border trade and the relevant legal issues (even though I am not a legal expert!).

Around this time, a well meaning colleague called me into his office and warned me, "This is not how we do things around here. Be warned, you could get into trouble." I thought little of his warning. But, he was right.

Several people lodged complaints about me because I did not follow procedures, and because DrEcommerce.com was not an official EU web site. So, I had to take down EU logos and not claim any associations with the European Commission in spite of doing the web site while contracted to the European Commission.

I was even invited to meet the very busy Director General of Information Society for a scolding. Interestingly, I was later told that the Commissionaire of Information Society appreciated what I had done (however, as I did not hear this from the Commissionaire himself and did not see anything in writing, I can not be sure).

At one point, a director pulled me aside and explained that within the Information Society Directorate of the European Commission, there was an entire unit devoted to communications and promotions. The head of that unit was apparently upset because Dr Ecommerce had brought more publicity and attention to the Directorate than her entire unit had done. Of course, that was in large part because she and her unit followed protocols and procedures which I had largely ignored. She had lodged at least two formal complaints about my approach.

Eventually, my contract ended and the problem was largely resolved. Others took over the Dr Ecommerce web site, but were obliged to stick more closely to procedures. Moreover, the dot-com boom had turned to bust and people were becoming leery about e-commerce. On top of that, Google was making it easier to find information on the web. So, not surprisingly, Dr Ecommerce eventually faded into disuse.

Post-Mortem

Was Dr Ecommerce a success? I'd like to think so, but it is hard to measure. The EU is not like a business where there are clear metrics, such as profit and loss, by which to measure success, innovation or anything else. That said, Dr Ecommerce brought loads of positive publicity; it painted a picture of a part of the EU being business aware and friendly (the stereotype among many is that EU officials are stodgy, out of touch bureaucrats keen on long lunches and legislative documents); and it provided loads of free information as well as useful advice to business owners and entrepreneurs. I believe it encouraged existing business owners to branch into e-commerce and motivated entrepreneurs to explore the possibilities of what was at the time a relatively new medium. I am sure I answered a lot of questions that helped people get started. Many of them thanked me for my help.

Was it innovation? I would argue it was. Providing a question and answer advice column on a web site, in which I answered questions ranging from how to accept credit card transactions on line to how to sell Nepalese handicrafts to the Japanese, was a bold concept for the European Commission. To answer questions in simple language and from a business (rather than bureaucratic or legislation-oriented) perspective was unheard of in the European Commission. At the same time, it enabled me to fulfill and even exceed my contractual obligations with relative ease.

Could I have done it had I followed procedures? Not really. I probably could have done some kind of question and answer web page on the European Commission server, but answers would have needed to be vetted and wrapped in EU jargon. Humour, especially if it poked fun at the Commission, would not have been acceptable. The result would surely have been a drab and forgettable resource.

Advice for Creative Thinkers in Bureaucratic Organisations

What my little adventure demonstrates is that if you work in a bureaucratic organisation and have a really creative idea, following the established approval processes may be a death sentence for your idea. At best, your idea will be so diluted as to be no fun any more. At worst it will be rejected altogether.

One way to avoid this is not to seek approval for your idea, but simply to do it. It's risky. If you do not succeed, you may get into trouble. Even if it does succeed, you may get into trouble. But, in a business where the success of ideas can be measured, usually in profits and losses, a crazy idea that works is likely to be adored once is shows signs od succeeding. Indeed, having spoken to people who have simply implemented ideas without approval, I hear a similar story. Initially there is resistance, occasional reprimand and eventually appreciation when the idea succeeds. Moreover, if the idea succeeds, people who were initially against it often try to claim credit for supporting it initially (this happened with Dr Ecommerce).

Breaking Rules

It is often said that creativity is about breaking rules. In some cases, the implementation of creative ideas so that they can become innovations is also about breaking rules. But in the case of innovation, there can be consequences. When you have an illegal idea, the question you need to ask yourself is, "Am I willing to take the risk?"