Why Voting for Ideas Is Stupid

Why voting in suggestion schemes does not successfully identify creative ideas.

With the growth of interest in innovation, a number of firms have recently launched suggestion scheme software products. These products make it easy for employees (in closed systems) or even the public (in open systems) to submit ideas about anything. The great thing about such suggestion scheme software is that, properly promoted, they can generate 1000s of varied ideas. The bad thing about such suggestion schemes is that, properly promoted, they can generate 1000s of varied ideas! After all, if you actually want to innovate, you have to devote resources to reviewing those 1000s of ideas in order to identify which ideas might become innovations. And without a structured innovation process behind the suggestion scheme, each idea needs to be individually reviewed.

Not long ago, in an unknown software company somewhere in the world, some bright spark had the idea to add a voting system to their suggestion scheme software product. On the surface, the logic seems good: with so many ideas coming into the suggestion scheme, why not let users of the system vote on ideas in order to identify the best ideas? Clearly the ideas with the most votes will be the best, after all they will have been elected following proper democratic due process. Then the owners of the system need only implement the ideas with the most votes and innovate like crazy.

There are two flaws with this seemingly lovely theory. Firstly, research in social psychological behaviour, group motivation and incentives demonstrate that the theory is completely wrong. Secondly, no one seems to have actually read up on the research and, as a result, nearly every suggestion scheme software company uses the same highly flawed voting system.

Let's look at the flaws.

People Do Not Vote on Best Ideas. They Follow Trends

Research has shown that in transparent systems where people can vote on submissions, their voting is based more on trends than on the quality of the actual submissions. Particularly interesting and relevant is a recent study by Matthew Salganik, Peter Dodds, and Duncan Watts, entitled “Experimental Study of Inequality and Unpredictability in an Artificial Cultural Market.”1

The researchers had 14,000 volunteers participate in a web based music download system. Participants were able to listen to songs from obscure bands, vote on how much they liked the songs and then download those songs.

Users were divided into groups. In the control group, users could not observe the actions of other users. They simply listened, voted and downloaded. The remaining users were divided into eight parallel worlds, each using an interface available only to other members in the same parallel world. In each of these worlds, participants could see which songs other members of their world had downloaded and watch the voting in real time.

In each group, a strikingly different collection of musical tracks was voted in as best. In the control group, the top choices were spread widely, with no one track getting a huge number of votes. And this was assumed to represent participants' actual liking of individual musical tracks.

In each of the worlds in which users could watch the voting results, something interesting happened. Users first listened to the tracks which had the most votes. In many instances, they also voted for these tracks and downloaded them. Moreover, they often did not even bother to listen to the tracks with no votes. This created a snowball effect, with a small number of tracks getting a high number of votes and many other tracks ignored.

Most interestingly, the top voted songs in each of the worlds were very different from one world to the next. Indeed, economists have long noted that this “network effect” occurs within populations.

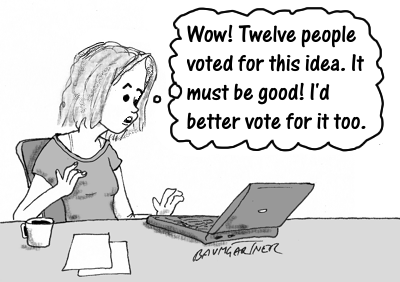

Think About It

If you stop and think about your own behaviour, you will see that this makes sense. Imagine you visit a suggestion scheme for the first time. You see that there are 100s or 1000s or more ideas in the system. Although the ideas are categorised, there is no logical order to them. Most likely you will initially look at the ideas with the most votes, assuming that these are the better ideas. And, if you like the ideas, you will vote in their favour. You probably will not want to admit it, but you will also very likely assume that highly voted ideas must be a good in order to have achieved their high scores. As a result, you will push up the popularity of the popular ideas but are unlikely to even have the time to look at the unpopular ideas.

If 100s of people behave similarly, it is no surprise that those ideas, which are submitted early and receive a few positive votes, quickly become the most popular. However, the most popular ideas are not necessarily those that have the greatest innovation potential. Indeed, if you look at typical behaviour in a brainstorming or other ideation event, you will realise that they are unlikely to be the most creative ideas. And remember, it is the highly creative ideas that are most likely to become breakthrough innovations.

Creative Ideas Come Last

If you have ever participated in a brainstorming exercise, you will know that the first ideas tend to be the obvious ones. By definition, then, they are not particularly creative and are unlikely to become breakthrough innovations. It is only after the obvious ideas have been exhausted that people start pushing their minds and being creative.

However, as we have seen, in an on-line system with popular voting, the first ideas are likely to capture the votes. As a result, more visitors will look at them and fewer will look at the latter, ideas which will not receive many votes. However, it is among those unpopular ideas that the most creative are likely to sit!

So, it is clear that voting in suggestion schemes does not identify the most creative ideas and may even act to hide those ideas. But it gets worse!

Topic Fixation

Topic fixation is a danger in any kind of brainstorming activity. In traditional brainstorming, it occurs when an individual suggests an idea that other brainstormers like. As a result, they suggest similar ideas and, as a result, you see a large number of very similar ideas being submitted with the further consequence that participants are not exploring other themes for ideas. This has been demonstrated empirically since the 1950s.

However, more recent research has shown that this happens in on-line systems too. Nicholas Kohn and Steven Smith of The University of Texas at Arlington, USA recently published a paper on "Collaborative Fixation: Effects of Others’ Ideas on Brainstorming”2. Rather than looking at traditional brainstorming in a conference room, the researchers put volunteers in front of computers and had them suggest ideas using AOL instant messaging software. In other words, they submitted ideas on line. Mr. Kohn found that “Fixation to other people's ideas can occur unconsciously and lead to you suggesting ideas that mimic your brainstorming partners'. Thus, you potentially become less creative.”

While this research used small groups and did not include voting, it would seem likely that voting for or against ideas would encourage topic fixation. After all, if an idea gets a lot of votes in a suggestion scheme, users are likely to assume that such ideas are best and will want to submit similar ideas – not realising that the best ideas received their votes as a result of the network effect rather than because they are actually the best. (Actually, rewarding the “best ideas” is also a flawed concept that leads to reduced levels of creativity in ideation activities.)

I have not yet come across research on this precise scenario. But, if you look at popular public suggestion schemes, you can certainly see not just similar ideas, but nearly identical ideas being submitted again and again and again. And this only adds to the workload of the administrators!

Conclusion

So, we can see that voting for ideas in suggestion scheme software encourages people to vote for ideas that achieve early popularity, usually for no better reason than that they were the first submitted ideas. Moreover, new visitors are likely to view only those ideas with the most votes, thereby being less likely to see, let alone vote on, more recently submitted ideas that are actually more creative (as a side note, most suggestion scheme software products do not identify how you should vote and those that do suggest you vote for the best ideas – see note above – rather than the most creative or the most unique). Finally, voting is likely, but admittedly unproven, to encourage topic fixation and result in a lot of duplicate and very similar ideas.

For administrators of suggestion scheme software, it is clear that voting will not make their jobs any easier. For submitters who know their ideas are more creative, but find their ideas are ignored, the result is likely to be frustration with the software and the suggestion scheme itself. Finally, users who see no correlation between votes and implementation; or who wonder why their popular ideas are ignored by administrators, there is also likely to be frustration and demotivation.

In summary, voting is actually highly detrimental to suggestion schemes. If you wish to have some kind of user interaction on quality, however, there are two approaches you can take. Firstly, rather than popular voting, use a sliding scale such as Amazon uses with book reviews. Users on Amazon can give between one and five stars depending on how good a book is. Moreover, ratings are based on the number of stars and not the number of votes. Secondly clarify that stars should be awarded for creativity, uniqueness, added value or a similar attribute that is relevant to innovation potential. While these simple actions cannot replace a structured evaluation of ideas, they at least make the user interaction more relevant to the aims of the suggestion scheme.

References

1) “Experimental Study of Inequality and Unpredictability in an Artificial

Cultural Market”; by

Matthew J. Salganik,1,2* Peter Sheridan Dodds,2* Duncan J. Watts; Science 311,

854 (2006); DOI: 10.1126/science.1121066 (http://www.sciencemag.org/cgi/reprint/311/5762/854.pdf

-- PDF document)

2) “Collaborative Fixation: Effects of Others’ Ideas on Brainstorming” by Nicholas W. Kohn1* and Steven M. Smith; Applied Cognitive Psychology; 29 March 2010 (http://www3.interscience.wiley.com/journal/123329584/abstract?CRETRY=1&SRETRY=0)